Thailand's Land Bridge Parallels Mexico's Interoceanic Corridor

Both countries have an opportunity to alleviate shipping chokepoints while boosting their own economies and geopolitical standing.

In 2021, the Japanese firm’s vessel, the Ever Given, became lodged in the Suez Canal blocking it for seven days and disrupting the narrow waterway which carries 12% of global trade. The public received a crash course in shipping logistics and they learned something the experts already knew, that the world’s shipping lanes are congested and vulnerable and becoming more so by the day.

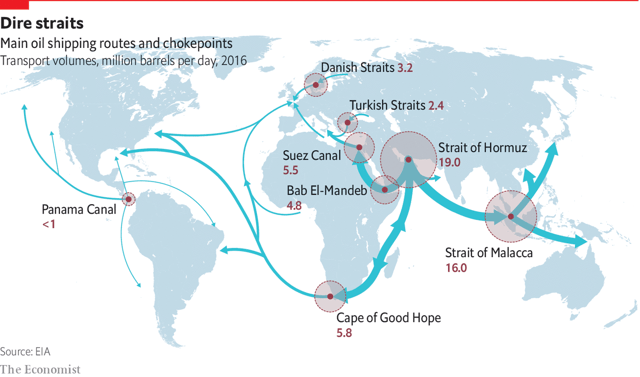

The eight shipping chokepoints (i.e., canals, straits) are getting worse because shipping lanes are busier, upgrades to existing chokepoints slow to occur, with new passageways mostly failing to go beyond the planning stage. According to the Economist, in 2010, 8.4 billion tonnes of cargo travelled by sea. By 2019, this had grown to 11.1 billion tonnes. In 2000, 42% of global grain exports passed through at least one maritime chokepoint, according to Chatham House, a think-tank. By 2015, the figure had risen to 55%.

Interesting to emerging market real estate investors is that two of the world’s eight chokepoints can be eased through the creation of land bridges in Mexico and Thailand. The two land bridges traverse narrow portions of the respective countries and are nearby the Panama Canal and Strait of Malacca chokepoints, respectively.

Emerging Real Estate Digest has previously written about Mexico’s Interoceanic Corridor, let’s now take a look at Thailand’s.

Thailand’s Land Bridge

Thailand’s proposed land bridge seeks to take advantage of congestion at the Strait of Malacca chokepoint, presently the shortest sea route to move goods from the Persian Gulf to Asian Markets. The 550-mile long strait runs past Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore and at its narrowest point is only 1.5 miles wide. Roughly a quarter, or 15 million barrels per day, of all oil transported by sea passes through this strait. It transports 80% of China’s oil from sea shipments.

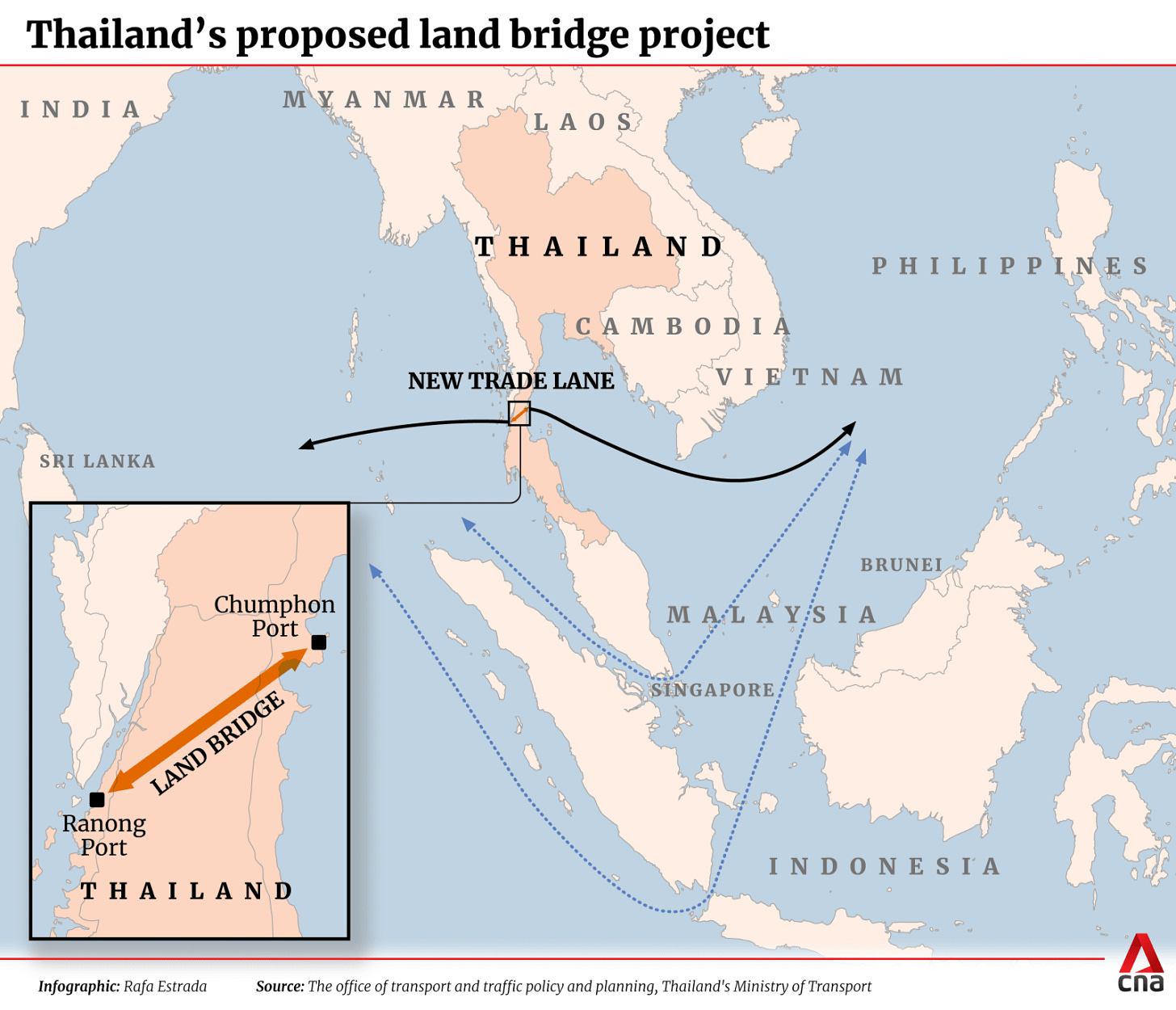

Thailand’s land bridge would bypass the congested Strait of Malacca by establishing two deep sea ports and linking them with 90 kilometers (i.e., 55 miles) of rail, road and oil pipeline networks. Shippers using the land bridge could expect to shorten shipping times by at least two days. Thai authorities estimate the project would boost annual GDP growth by one to two percentage points annually.

If, and that’s a big if, Thailand can get this right, it could establish itself as a global shipping hub similar to nearby Singapore. Vietnam is making moves to do something similar by recently starting to make direct sea shipments to America putting itself in direct competition with Dubai, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Singapore. Further value is planned to be unlocked by connecting the new land bridge to the exceptional manufacturing hub in the Eastern Economic Corridor. The oil fields in the Gulf of Thailand could be more quickly and fully brought online and oil transported to foreign purchasers via the new infrastructure and connecting it to other projects already completed and planned.

Obstacles to Overcome

The challenges to successfully bring the new land bridge to reality boggle the mind, but aren’t technically insurmountable. I use the word “successfully”, because building the land bridge alone is not sufficient and risks creating a glittering metallic white elephant in the middle of Thailand’s least developed and most dangerous region.

Cost. The price tag of between $27 and $35 billion are massive figures for a country like Thailand. Even China’s Belt and Road Initiative would struggle to make a dent in the financing need. Most of the costs are associated with establishing the two deep-sea ports in Ranong and Chumphon, and the oil infrastructure to hold and pump out the liquid gold received from oil tankers from the Andaman Sea and Gulf of Thailand.

China and America tug of war. China’s financial and operational involvement would raise ire from the increasingly irrelevant Washington DC, and more importantly from nearby Asian neighbors. Thailand inserting itself and challenging shipping incumbents in the region, at this moment, is unlikely to end well for Thailand. Sabotage, piracy and other similar shipping disruptions are more likely now that the American navy is removing its protection guarantee of shipping lanes the world has enjoyed gratis since the end of the second world war.

Separatist Movement. Many in the south of Thailand, in the undeveloped and poor areas where the land bridge would cross, favor separating from Thailand. The separatists could cause construction delays and cost overruns. One reason a canal isn’t on the table is because it would physically split the country into two which could give rhetorical and legal fodder to the separatists.

Increased Coordination. Ships would need to be unloaded and reloaded, and some may rather prefer the longer journey through Singapore requiring fewer logistics steps and risks. Delays could easily exceed the potential time and cost savings associated with using Thailand's land bridge.