Pension Fund Contribution Rate Volatility

Diversification and higher return objectives alone don't explain pension funds' growing exposure to private equity real estate funds. Contribution rate volatility is rarely considered as a factor.

The growing interest in private equity by America’s pension funds is generally attributed to two factors: 1) higher returns, and 2) diversification. While not incorrect, there is more at play, such as the desire of pension managers to smooth out contribution rate volatility, which is the topic of this edition of the Emerging Real Estate Digest.

America’s pension funds manage an estimated $23 trillion of capital on behalf of their beneficiaries. That’s more than all other countries combined. 11% of the total allocations are in Real Estate funds. Another 11% is invested in all other private equity categories including Buyout, Venture Capital, Fund of Funds, Co-Investment, and Secondaries.

Higher Returns

When a pension fund manager generates healthy returns, he increases the likelihood that future pension liabilities will be met. Higher returns are associated with more volatility, and according to Modern Portfolio Theory, risk is (absurdly?) defined as volatility.

The expected returns of private equity fund managers fall short of the returns realized. Emerging Real Estate has previously written about why private equity underperforms, particularly real estate funds. One would therefore expect allocations to be decreasing to real estate private equity, not increasing. Pension funds continue to be the biggest backers of real estate funds, with no signs of slowing. Returns alone aren’t shaping investment decisions at America’s pension funds, more is at play.

Diversification

There is a famous saying in investment circles and it is that “diversification is the only free lunch” available to investors. This quote is from Markovitz, the founder of MPT, and is in direct conflict with what your grandmother told you often that “there is NO such thing as a free lunch”. So who is correct?

Markovitz argues that a portfolio should contain numerous uncorrelated assets, meaning that when one asset category goes up, another goes down. If each uncorrelated asset category has the same expected return, the risk-adjusted return of the portfolio is magically increased (i.e., a “free lunch”) because volatility has been decreased through diversification and the expected return has remained the same.

The problem here, and why your grandmother was right (yet again), is partially explained by Charlie Munger in the below YouTube video clip. As with returns, diversification alone doesn’t explain why America’s pension funds are increasing allocations to private equity real estate funds. Asset categories are more correlated than in the past, and the private company diversification claim is in doubt.

Contribution Rate Volatility

Contribution volatility alludes to changes in the amount a public pension fund participant is required to contribute annually to his defined benefit retirement plan. The required contributions are based on the Actuarially Determined Contribution (“ADC”) tables which fund actuaries generate. Actuaries weight several factors to determine the likelihood that future pension liabilities will be met, and their analysis determines the magnitude of any increases or decreases in the participants’ contributions for the period.

The only way the actuaries can make the numbers work is to either increase participant contributions, or portfolio returns. The relationship is that when portfolio performance is higher than anticipated, participant contributions are reduced. When returns are lower than anticipated, the converse occurs and the participants are notified that they must now pay more as a result.

Pension fund managers smooth out contribution rate volatility in a number of ways. One way is to build up a cushion of cash by not lowering contribution requirements when the portfolio outperforms. Those surplus contribution payments are theoretically then available to be used to offset future contribution rate increases during bear markets. Another technique is to recognize portfolio gains and losses over a five-year period, or longer.

This brings us to the main event, which is that private equity offers characteristics which aid a pension fund manager in smoothing out contribution volatility.

Private Equity and Contribution Volatility

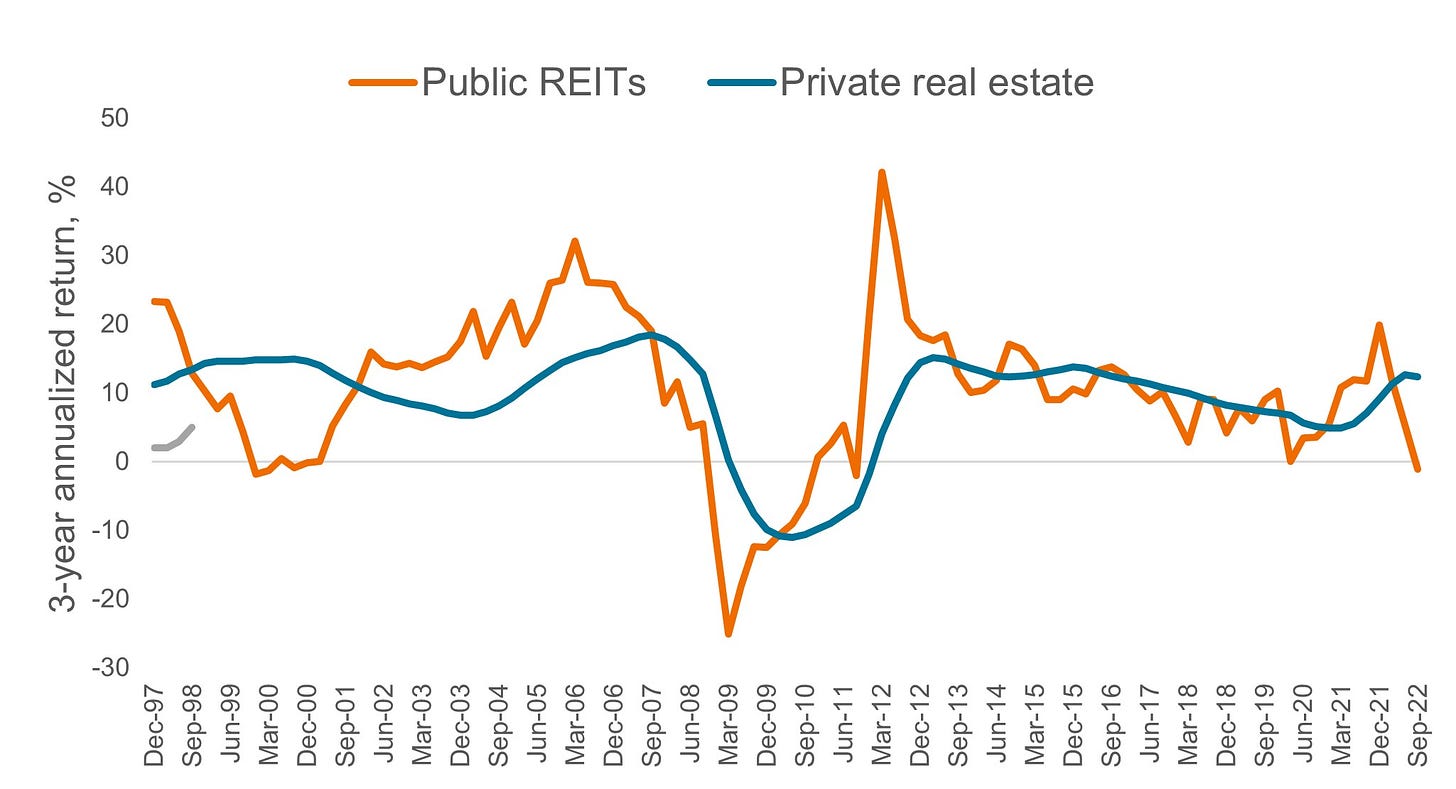

A REIT will have more volatility than a real estate private equity fund, even if we assume the exact same properties are held in each. And as stated, this leads to increased portfolio volatility, which is positively correlated to contribution rate volatility. One reason for the heightened volatility is because REITs are marked to market, which means that the valuation of the investment is determined based on the last purchase price of the shares on the exchange (i.e., market price of REIT share * shares outstanding). Funds, on the other hand, value the real estate investment based on a sum of the parts analysis on the entire portfolio. The NAV valuation methodology, based on cap rates and NOIs, will be much smoother (i.e., less volatile) than the marked to market methodology REITs are required to use.

The result for the pension fund, in this case, is a lower volatility (i.e., risk) portfolio and thus higher risk-adjusted expected returns. This is achieved simply by changing the vehicle in which the properties are held. That the NAVs of properties in a private equity fund may only be valued once or twice per annum works to further smoothen. Office REITs are trading at a huge discount to NAV, somewhere around 60%. Were these office properties held in a fund structure the outcome would be different.

Another way private equity real estate investments help reduce contribution rate volatility is the manner in which the future returns are amortized. Since all of the gains come at the end, say in year ten, the pro rata share of the expected gains are taken each year, according to the amortization schedule. The more the portfolio is exposed to private equity, the more “certainty” there is in the portfolio which means less volatility. REITs don’t have this advantage, they are marked to market and dividend payers.

A potential ticking time bomb in the portfolio of many pension funds in America is that they may be holding materially overvalued interests in private equity funds. Having already realized these gains in previous years, the correction could be disastrous.