Part 3: Real Estate Private Capital Series

The shortcomings of using private equity for real estate investments, both in developed markets, and those found in Latin America and Africa.

In this four part series we will look at the role of the private capital asset class in real estate investing. Where it’s been, where it’s going, and where the future opportunities lie. Part four will give actionable intelligence you can act on today to get in front of the next wave of private capital into Latin America and Africa real estate investments.

The four parts of the Private Real Estate Capital Series:

The shortcomings of Private Equity for Real Estate Investing

Positioning yourself for the next wave of private capital flows into Latin America and Africa

Returns for private equity, net of fees, do not generally outperform the overall equity markets, as measured by indices such as the S&P 500. Gross returns for private equity are higher, and private equity does offer diversification, but in most cases the high fees (3%-4% off the top), misalignment of interests, and illiquid nature of the investment structure outshine the benefits.

In spite of those limitations, and more which are discussed later, the private equity investment structure has flourished. There are several credible theories as to why this is the case, and the one I find the most persuasive is presented below.

Private Equity’s Protective Ecosphere

Professor Hooke is the author of The Myth of Private Equity: An Insider Look at Wall Street’s Transformative Investments, and in the book, he describes private equity as being protected by an unintentionally formed “protective ecosphere” premised on a web of overlapping interests by the industry participants. He argues that the asset class is generally detrimental to investors, and that if the protective umbrella was removed, the asset class would greatly diminish in prominence.

“[private equity] is a current manifestation of the irrationality that grips Wall Street from time to time.”

-Jeffrey C. Hooke, Johns Hopkins Professor

Is the protective ecosphere real? Or simply a conspiracy theory?

You can answer that question for yourself after reviewing Professor Hooke’s argument. Some of the main players in the protective ecosystem he outlines are institutional investors, institutional managers, consultants, regulators, and the media.

The boards of America’s institutional investors are intelligent people but rarely are they themselves sophisticated investors. Appointments are often political, and for a term. The high fees, neutral performance, and misalignment of interests between the private equity manager and the investors’ beneficiaries are therefore tolerated because the members either don’t understand properly, or they simply go along to get along. These bodies are aimed at supervising the institutional fund managers, ensuring investments are aligned to the interests of beneficiaries, but too often they aren’t able to perform this function, or don’t.

Institutional money managers benefit from allocating to private equity. The allocation to private equity makes it harder to compare the manager’s performance to the indices. This is important because these institutional fund managers are very well paid ($2 million+ p.a.), and yet the vast majority rarely perform better than the broader market. The added complexity of exotic investments work in favor of the manager to justify his existence and juicy reward. Private equity valuations tend to be smoother over time since the valuations are not marked to market. This means the manager’s portfolio will have the appearance of being less volatile if it contains chunks of private equity.

Consultants are incentivized to recommend private equity. Fees are higher for advisors of exotic and alternative asset classes, than for those who recommend listed stocks and funds. Portfolios of private equity funds are valued by third parties, and not marked to market. That means real-time performance data on the portfolio is difficult to know with certainty. Most exits occur seven to ten years after the investment has been made, and it’s only then that the investor truly knows if he has made a mistake trusting the consultant’s advice.

Regulators are largely absent. The trillion-dollar private equity industry is hardly regulated. Proponents will argue this is reasonable because the investors are sophisticated, and the public markets aren’t being utilized. Skeptics of self-regulation might point to the political contributions and lobbying fees paid by the industry annually. A cozy relationship between regulators and dominate industries is never preferred if the goal is a well-functioning economy within a constitutional republic or democratic government framework.

Media plays a role. The finance media rarely causes any discomfort for private equity firms, in fact they do the opposite when they create sexy headlines praising the latest mega capital raise or acquisition. There is much they could cover and expose to analysis and public consumption, but they don’t. Private equity firms are significant funders of advertising for America’s media. They also in many cases, directly and indirectly, own or control many of the major media, PR and communication companies which inform the public.

Listen to Professor Hooke break all this down in more detail. 👇

Real Estate as a Private Equity Target

Real estate private equity funds face unique challenges and potential downsides, over and above those already discussed for private equity in general.

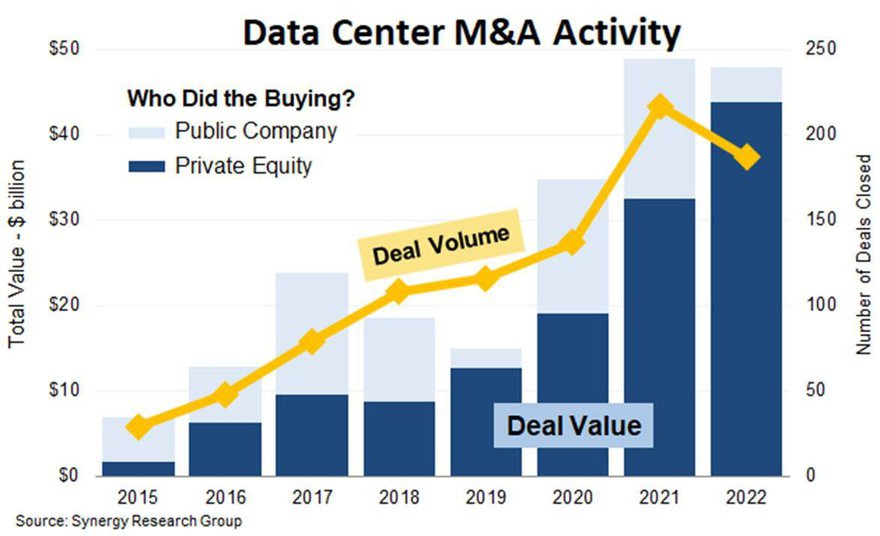

Real estate and high returns. It’s difficult for private equity to make the required returns when real estate is the target. Taking development risk, loading the projects with high debt levels, and buying properties without stabilized NOIs to later flip are three common equity enhancement strategies utilized. In pursuit of high returns, managers have been accused of holding properties for too long waiting for the “black swan” event to occur which is sometimes required for performance bonuses to kick in. They have also been known to overload projects with debt, and other forms of risk, in order to meet return expectations. Sometimes, the industry bites off more than it can chew, and finds itself in the position as the primary M&A actor in the industry. I’ve previously written about the datacenter real estate fad driven at the end by overzealous private equity investors.

Real estate is illiquid. The private equity model gives the appearance of liquidity for real estate investments since after seven years the committed capital is supposed to be returned with profits. Some studies indicate that nearly half of the properties purchased by older vintage private equity funds are never sold in a market transaction for cash. Instead, the real estate held by the fund might be exchanged for shares of an outside entity at a valuation agreed by the managers. These non-market related transactions make it difficult to assess the actual value real estate private equity managers have contributed to investors over time. In other cases, the unsold properties (i.e., zombies) simply remain in the fund until they are sold, sometimes at steep discounts of 30% or greater.

Private equity turned real estate investing into a national game. In the past, a local developer would put together a project, and fund it at the local or regional bank and collect the equity from as many wealthy families in the community as was required. The local participation in real estate projects deterred excesses and had other positive impacts on the community. Now, those local wealthy families likely have spent their real estate allocation with a national private equity firm. The allure of the snazzy presentation and charts, pedigreed managers, and promises of higher returns and geographical diversification can be difficult to resist.

Application to Latin America & Africa

The aforementioned issues are only amplified when the property is located in challenging markets, such as those found in Latin America and Africa.

Investors expect higher returns given the higher perceptions of risk associated with the foreign country and its currency. This places the manager in a difficult position in cases where the original investment thesis comes under pressure,

Debt is expensive and difficult to include in capital stacks in some markets, and this is a problem because debt is a primary way of creating value for real estate equity investors,

Exits for large real estate projects in the markets are much rarer than in those more developed, and

Pressure to deploy capital in three years can serve as a positive motivator in markets like America, whereas developing markets have a tendency to punish those moving too quickly and reward patience.

Positive Private Equity Reminder

Recall that the purpose of this part of the series was to show the downsides of the private equity asset class for making real estate investments. Some of the finest, most professional, and honest people I know work at private equity firms. These firms will continue to have a place in making real estate investments.

Let’s call a truce and meet in the middle.

Positives of private equity:

Private equity in real estate was an improvement to the old way institutional funds engaged outside managers and offered a better aligned solution,

Pooling capital allows the managers to take advantage of scale and deliver outcomes which otherwise might not be possible,

Large scale ownership of real estate holdings through private equity facilitated the creation of more REITs, and

Private equity excesses can be better attributed to lack of regulatory involvement, and alignment issues inherent to the structure, rather than misfeasance by private equity firms.

Next Saturday: positioning yourself for the next wave of private capital flows into Latin America and Africa real estate. I hope you’ve enjoyed it so far and found value!