Part 2: Real Estate Private Capital Series

Private equity real estate funds arrived late to the party in 1988. The asset class was birthed in an environment which parallels today.

In this four part series we will look at the role of the private capital asset class in real estate investing. Where it’s been, where it’s going, and where the future opportunities lie. Part four will give actionable intelligence you can act on today to get in front of the next wave of private capital into Latin America and Africa real estate investments.

The four parts of the Private Real Estate Capital Series:

Real Estate Private Equity Emerges

The shortcomings of Private Equity for Real Estate Investing

Positioning yourself for the next wave of private capital flows into Latin America and Africa

Real Estate Private Equity Emerged Late

Last week we learned that modern private equity’s first expression was through venture capital following WWII. Private Equity, as we conceive it today, arrived in a big way starting in the 1980’s through LBOs.

It wasn’t until eight years later, in 1988, that the first real estate private equity fund was established. That it took so long for real estate to become an LBO target is surprising given the usually large transaction size, and that real estate has relatively stable cash flows. Attributes the junk bond market values.

The issue wasn’t lack of interest from investors, rather it was lack of need by the developers and property owners for the capital. Banks were offering non-recourse loans, often at LTVs approaching 100% of the project cost, and the cost of the capital was relatively low. Why speak to Gordon Gekko when your friendly neighborhood banker was writing blank checks on favorable terms?

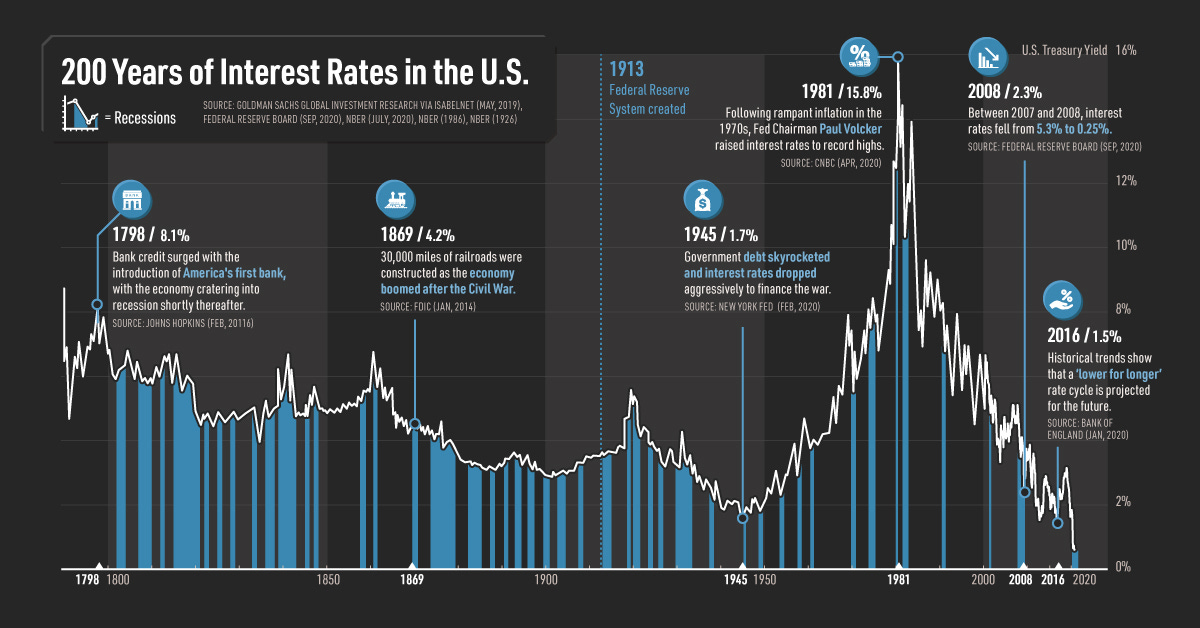

This began to change in the mid-1980s as real estate came under distress and foreclosures became more common. The dramatic rise in interest rates in the 1970s and early-1980s, caused banks to reassess their lending requirements, given the amount of bad loans they found themselves holding. LTVs went from 90%-100%, to only 50%-70% in the early 1990s. You’re probably noting the parallels to recent changes in today’s lending environment.

At first, this wasn’t a problem. Real estate developers were able to raise the additional equity in part by selling tax losses to professionals, such as dentists and doctors, to shield their professional income from taxation. This was made possible by U.S. income tax laws which permitted 15-year depreciations on real property. The compressed depreciation schedules assured an early “loss” which could be easily sold even before construction began. In 1986, the Tax Reform Act was passed, extending depreciation schedules. The effect was dramatic, real estate prices fell, and equity became harder to come by for real estate developers and purchasers.

In this period, holders of equity for real estate went from zeros to heroes. The stage was set for the first real estate private equity fund to emerge.

Zell-Merrill Fund

Sam Zell is credited with starting the first private equity fund focused on real estate investments in 1988. It was called the Zell-Merrill Fund. The Merrill part of the name is from the company formerly known as Merrill Lynch, having recently been rebranded back to Merrill by its parent, Bank of America.

Fundraising for the fund was brutal, but through perseverance the fund’s commitments of $10 million in May, mushroomed to $408 million by June 30, 1988. The fund’s final close was $490 million. The sponsors contributed $40 million, representing around a 10% GP commitment.

The fund’s strategy was to purchase prime properties which were about to be, or had been, foreclosed. In some cases, the fund would contribute just enough capital to see the loan on the property to conclusion. The banks avoided a write-off, and the fund took the property. Sam Zell’s fund was one of the only cash-rich purchasers of properties during this period, giving him the pick of the litter.

A related strategy was to buy prime properties from the U.S. government which it had come to control through its role in “saving” failed banks in the Savings & Loan Scandal and Crisis of the late-1980s. Again, a parallel to what we are seeing today.

The returns on this first fund weren’t spectacular. Three subsequent funds in the series were raised, and they performed better. Those funds raised $410 million, $680 million, and $688 million, respectively. The four Zell-Merrill funds were consolidated creating the Equity Office REIT, which was later sold to Blackstone in 2007 for $39 billion.

More GPs Enter the Fray

Goldman Sachs was next. The investment bank realized it could make more money investing in real estate rather than collecting advisory fees advising on dispositions. Its first real estate fund, the Whitehall I Fund, closed in 1991 with commitments of $166 million. The second fund in the series, Whitehall II Fund, closed the following year and managed to raise a much larger $790 million. Goldman continued raising Whitehall real estate funds and closed the series in 2019 after raising $22 billion across thirteen Whitehall funds.

Early real estate private equity funds were primarily funded by wealthy individuals and families. The institutional investors, at the time, were satisfied with their current real estate exposure, and many had been burned in the terrible real estate environment which made it possible for real estate private equity funds to emerge in the first place.

Other established and new GPs followed the efforts of Sam Zell and Goldman Sachs and successfully raised their own real estate funds. These investment companies included Angelo Gordon, Apollo, Blackstone, Cerberus, Lehman Brothers and Morgan Stanley, AEW, Colony, JE Roberts, Lone Star, Lubert-Adler, O’Conner, Starwood, Walton Street and Westbrook. In 1992, Merrill Lynch took public a strip shopping center development owner creating Kimco Realty, now the largest open-air, grocery-anchored retail REIT in the world.

Private Equity was an Improvement

Before real estate private equity funds, institutional investors hired specialized real estate managers to invest their capital through separate accounts and commingled funds. Fees were based on percentages of NAVs, and commissions were paid on concluded transaction. There was, therefore, a strong financial incentive to transact frequently and to report the highest possible property value as possible.

The practice was exposed in the early 1990s when institutional investors realized that their managers had been reporting valuations higher than was justified. The reality was that the property values were collapsing.

The private equity model was an improvement over the status quo because it better aligned the interests of the investor and outside manager. This was achieved in a few ways including the practice of GPs committing 2% - 25% of the total capital raised. By having skin in the game, the investors believed the managers to be more aligned to their interests.

Secondly, management fees for funds were based on committed capital, not NAVs. This removed the incentive to overstate property values in order to increase management fees. Lastly, commissions were abolished, and in their place a performance fee (i.e., carried interest) which only became payable after the investors had achieved a target return of capital and profits (i.e., hurdle rate).

Next Saturday: everything has a downside, and next Saturday we’ll discuss the drawbacks of using private equity to make real estate investments, particularly in challenging markets such as those found in LATAM and Africa.

Please tap the 🤍 and make it a ❤️.