Part 1: Real Estate Private Capital Series

In a relatively short period of time the private equity asset class has ballooned to $13 trillion of AUM and is predicted to nearly double to $23 trillion by 2026. How did we get here?

In this four part series we will look at the role of the private capital asset class in real estate investing. Where it’s been, where it’s going, and where the future opportunities lie. Part four will give actionable intelligence you can act on today to get in front of the next wave of private capital into Latin America and Africa real estate investments.

The four parts of the Private Real Estate Capital Series:

History of Private Equity

Real Estate Private Equity Emerges

The shortcomings of Private Equity for Real Estate Investing

Positioning yourself for the next wave of international private capital flows into Latin America and Africa real estate

Credit and Direct Equity Investments Ruled

1600 - 1946

In the beginning, there was credit.

For most of known history, ventures of all sorts were primarily funded through the extension of credit. Regulations protecting equity investors were sparse, unenforceable, and an investor could never truly know where a business stood financially. The invention of the cash register in 1879, in Dayton, Ohio, helped give some assurances. But not enough to give confidence to investors that their capital, and share of profits, wasn’t being embezzled or otherwise misused. Credit overcame many of these challenges.

For most of this period, there wasn’t a legal concept of limited liability. New York was an early advocate of limited liability laws and their early adoption explains partially why New York City became such an economic powerhouse. New York adopted limited liability laws in 1811, and it wasn’t until 1854 that Britain, the world’s top economy then, followed suit.

Lack of limited liability meant investors had personal recourse against the entrepreneur in the event the company failed. This favored credit over equity. Thankfully, debtors’ prisons are a thing of the past! Unlimited liability to company owners meant that the equity investors themselves would be liable, as owners of the business, for any obligations not able to be covered by the business. Receiving shares in a company through an equity investment, therefore, was seen as risky and only considered where family and close friends and business associates were involved.

Direct Equity Investments

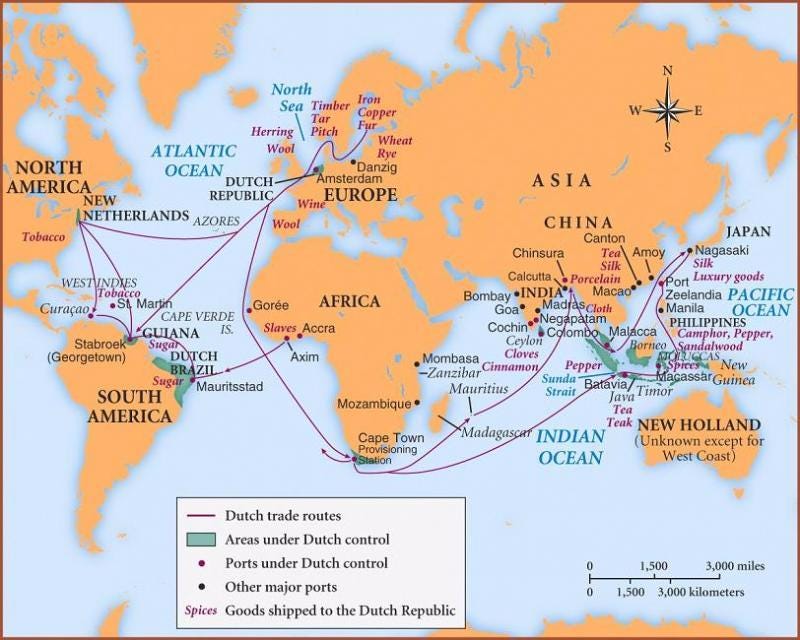

Shipping was one of the handful of industries which received direct equity investments prior to the advent of limited liability being codified. One of the biggest companies in that category was the Dutch East India company. Ships carrying goods to and from far away destinations, were funded by selling share certificates to equity investors. When the ship returned, the profits would be distributed to the investors on a pro rata basis. If the ship didn’t return, the investors lost their investment and had no recourse.

🎓 Trivia alert:

The term “carried interest” is thought to have originated from the practice of ship captains retaining a 20% commission on the goods they carried in successful shipments. Ship captains, and their crews, where the GPs of those days.

The advent of limited liability made possible the creation of a deeper and wider equity investor market. These early equity investments remained almost exclusively in the domain of the ultra-wealthy. One exception was the railway investment frenzy in Britain in the 1840s, where retail investors participated heavily. Railway investments were seen as safe because of the underlying land and equipment which secured the investments.

By the beginning of the 20th century, securitized equity offerings to the public were not uncommon. These offerings were almost exclusively underwritten on companies with substantial tangible assets on the balance sheet (i.e., railways). Large retail companies, with strong earnings and future financial prospects, were also attractive investments to the general public given the perceived low level of risk and that recourse would be available.

Venture Capital Fills a Gap

1946 - 1981

Following the Second World War, America’s challenge was to convert a war machine economy into a consumer goods economy. The financing frameworks of the day simply weren’t sufficient to fund this societal shift. The ultra-rich were too few and with too little capital. The retail investors could only be relied on to fund established businesses, which wasn’t what was required.

Venture capital, a subset of the private equity asset class, emerged and filled the funding gap. Venture capital funds permitted the pooling of risk capital from many sources. This capital was patient and prepared to take the types of bets the economy needed at that time. Many investors could contribute a portion of the total capital raised, and the scale achieved meant a team of professional money managers could be hired to allocate the capital to the most worthy ventures, and stick around long enough to achieve exits.

The first modern venture capital fund was formed in 1946 and was called the American Research & Development Corporation (“ARD”). It raised a sizable fund and was judged to be a success given one of its portfolio company exits. That exit occurred in 1957, and in today’s dollars would have been valued at $355 million, representing a return of 500 times the initial investment and an annualized rate of return of 101%.

Funding for the early venture capital funds came from wealthy individuals, other technology companies and the military-industrial complex. Pension funds only invested later, when in 1978, the Department of Labor changed its rules and permitted retirement funds to invest in private equity.

Leveraged Buyouts

1982 - 1993

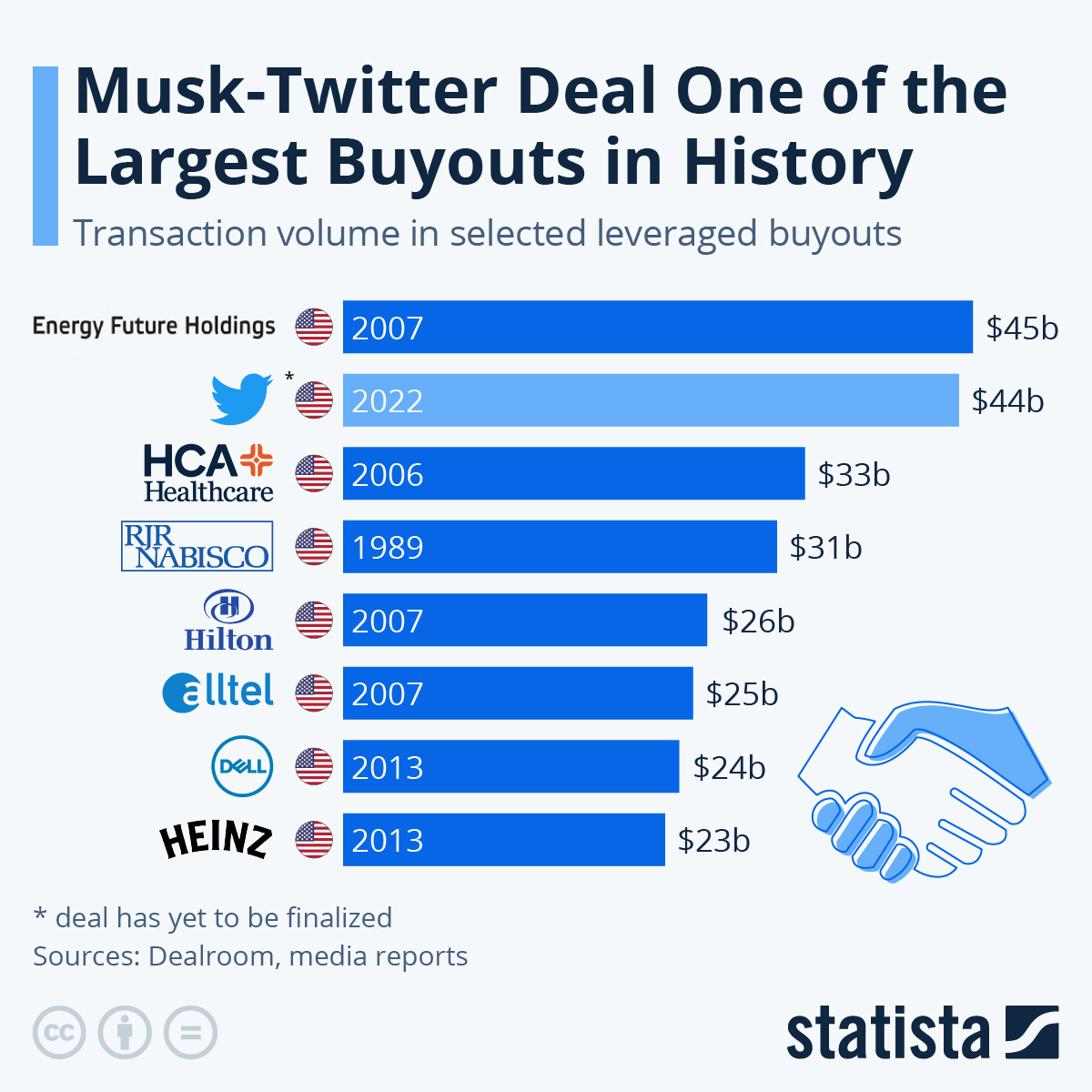

Leveraged buy-outs (“LBOs”), another subset of the private equity asset class, rose to prominence in the early 80s. LBO transactions involve acquiring a target company, and doing so with high amounts of debt. The secured debt is usually collateralized by the company being acquired, and the rest from issuance of junk bonds. The value LBO investors add is their willingness and know-how to cram as much debt onto the target’s balance sheet as possible.

Some clever economists realized in the 50s, and won the Nobel Prize for their discoveries, that adding debt to a capital stack created value for the equity investors in two main ways. The first is that the returns achieved in excess to what is owed to the bank, in the form of interest and return of capital, is available to the equity investors as a sort of “free money”. The second is that because interest is tax deductible, and usually a very large expense when LBOs are involved, the tax savings represent a value enhancer.

After a series of high profile bankruptcies, caused by the over-levered nature of the companies created by LBO investor involvement, the popularity of the investment theme waned. RJR Nabisco was the largest and most publicized such LBO failure. Public sentiment turned negative on the industry, investors shied away, and public companies began protecting themselves with measures such as poison pills in order to block hostile takeovers from LBO raiders.

Private Equity Rises From the Dead

1993 - 2007

Private Equity raised $20.8 billion from investors in 1992, eight years later in 2000, the industry raised $305.7 billion. The rise was made possible by favorable economic conditions, but also because it had repaired its damaged reputation. Time heals all wounds, and the public isn’t known for having a long memory. The 1987 movie, Wall Street, describes well how the industry was perceived and what had to be overcome from a PR standpoint for the asset class to emerge again.

Venture capital continued to zoom to new heights, only to be humbled, temporarily, by the tech bubble burst. By 2003, the venture capital industry company values had become worth about half of what they were only two years earlier in 2001. LBO activity also slowed. For the first time in history, in 2001, Europe had more LBO transaction volume than America. That year, Europe concluded $44 billion of deals, while the American counterparts only managed to close $10.7 billion.

The LBO industry was given a lifeline in 2002 with the passage of Sarbanes Oxley. The bill was aimed at increasing scrutiny on public companies as to how they manage and report financial performance. It also extended personal liability to public company executives and imposed other rather onerous duties. Public companies and their executives suddenly had an incentive to go private and private equity stepped in to facilitate the privatization of those effected public companies. High-flying technology companies with plans of an IPO, also became open to discussions with private equity firms. Enormous LBO deals were concluded during this period.

Private Equity Owns the World

(2008 - Today)

Private equity’s main problem is they now own most of the world. I’m being facetious, but in a way it’s true! There aren’t many large companies, suitable for purchase, left for them to participate. A symptom of this scarcity is the degree to which private equity chases hot fads. One of those fads was the data center investment bonanza, spurred on by overzealous private equity firms, which I’ve previously written about and can be found here.

LPs complain about the fees, returns, and misalignment of interest inherent to private equity. And although they keep plowing capital into the large private equity firms’ coffers, at some point they may decided to get off the merry-go-round. The wheels are in motion to replace a portion of any tired, rebellious and PE-skeptical LPs with smaller individual retail investors. That’s where I think much of the future funding of private equity will have to come from if the industry wishes to continue current growth trends.

Next Saturday: the story of how real estate private equity emerged. Sadly, a leader of the first ever real estate private equity fund, the Zell-Merrill fund, died this week at the age of 81. Sam Zell lived a remarkable life. I encourage you to research his life story and achievements if you haven’t already.