Coworking Is Not The Holy Grail

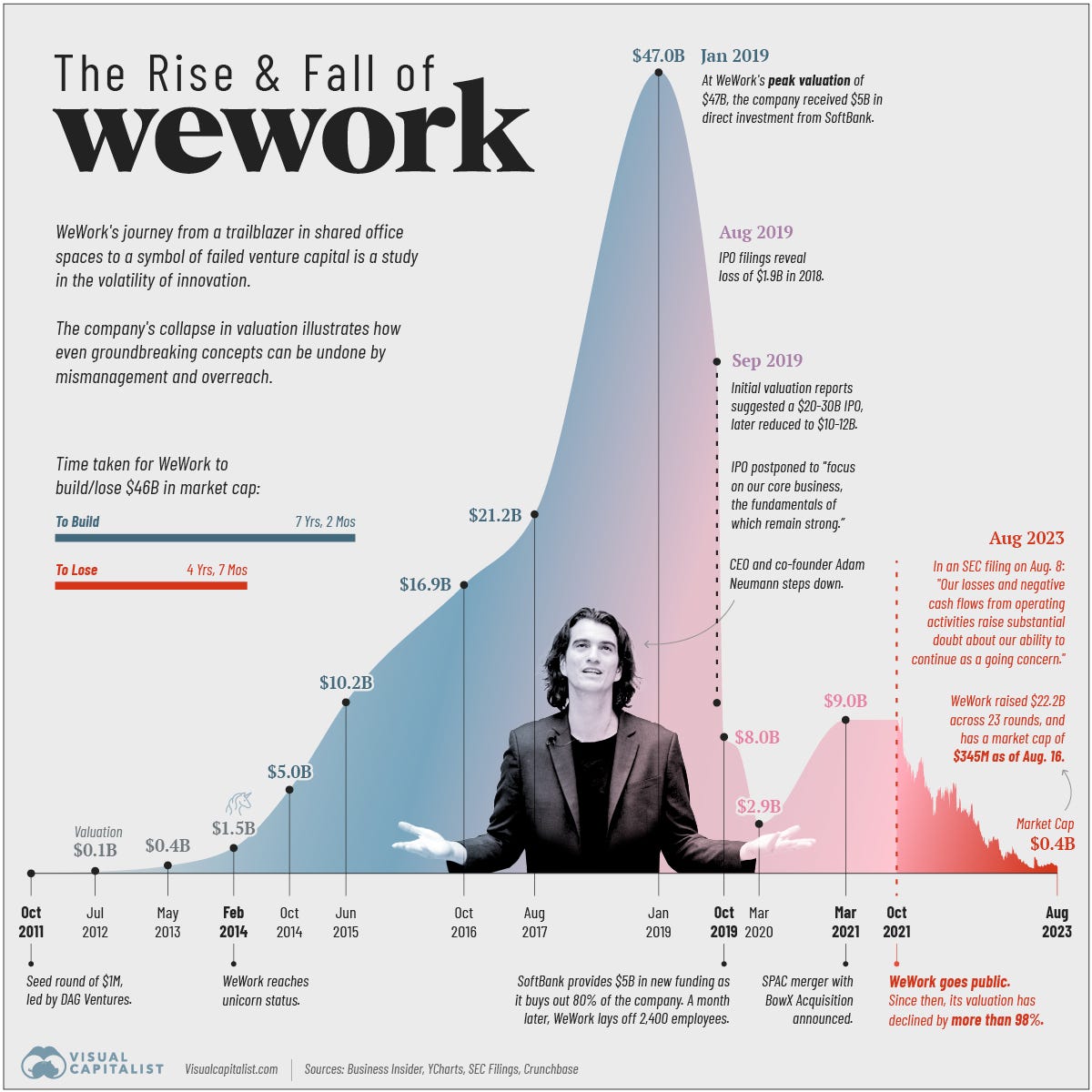

WeWork's demise is a reminder to return to fundamentals and that running with the herd is rarely the best course of action.

The biggest news in real estate this week was the Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing by WeWork. Let’s take a look at the coworking office business model and what we can learn from WeWork’s demise.

Coworking in Not the Holy Grail

The coworking model is premised on the generally unattractive business tradeoff of taking on one big long-term liability, and offsetting that with many assets composed of a bunch of short-term leases. That’s all coworking is. The business model has been unceremoniously operational since at least the 1950s. Most have failed, the survivors mostly marginal businesses. The legend Sam Zell did his best to inject sanity during the peak of the WeWork frenzy, but his level-headed interventions were not enough to stall the hype machine that by then was firing on all cylinders.

Offsetting long-term liabilities with short-term leases works only so long as there isn’t an office oversupply or recession in the economy. Both scenarios create downward pressure on rents and terms achieved on new short-term leases signed, meanwhile the long-term obligations stay the same. The coworking offering is easily replicated and a competitor only need lease a large space, cut it up into smaller chunks, add an aesthetic, and go to market. WeWork attempted and failed to create moats by quickly gobbling up and fitting-out prime real estate sites using its seemingly endless supply of venture capital backing.

In 2019, WeWork had $47 billion of lease obligations on the books being offset by only $3.4 billion of signed leases with customers. Confounding this very serious asset and liability mismatch was the fact that WeWork’s liabilities to secure real estate extended for fifteen years on average, while its customers were committing to spaces at an average duration of only fifteen months.

Venture Capital’s Role

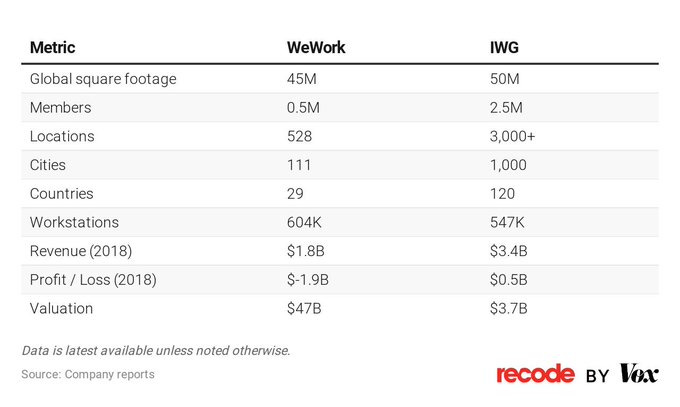

IWG is a Swiss-based firm which owns the popular and enormous coworking brand Regus. When WeWork was flying at its highest levels it had a valuation of more than 10x that of Regus, and this is in spite of Regus having more locations, revenues and actually being profitable, a feat WeWork never achieved.

WeWork justified the valuation gulf between it and its main competitor by claiming to be a technology company and not a real estate company like Regus. In its 2019 failed IPO, WeWork used the word “tech” 123 times in public filings. Here’s a sample from the S-1 filing:

“Technology is at the foundation of our global platform,” reads the WeWork filing. “Our purpose-built technology and operational expertise has allowed us to scale our core WeWork space-as-a-service offering quickly, while improving the quality of our solutions and decreasing the cost to find, build, fill and run our spaces.”

Adam Neumann, the former CEO and founder of WeWork, probably receives too much blame for the WeWork debacle. After all, it was the venture capital investors who enabled Adam and stuffed his pockets with treasure beyond belief with few guardrails in place to contain the brash, impulsive and immature founder. Much of the animus directed at Adam springs from the fact that he left WeWork a cash billionaire. This doesn’t jive well with the public who see Adam as a loser in his quest to build WeWork into a viable company, and therefore not deserving of such a handsome payout.

We are in an era of plentiful capital chasing a small number of deals, which often forces entrepreneurs to turn their ventures into shiny objects and dance a jig to have any hope of raising capital. This is what Adam did and he quickly learned that the more outlandish his claims and projections, the more love and capital venture capitalists showered him with. He was their golden boy, or put another way, their Frankenstein.

WeWork was backed by major investors including Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, SoftBank, Benchmark, T. Rowe Price, Fidelity, Hony Capital, Jefferies and Legend Holdings. The well-heeled and sophisticated investors not only bought into the story that WeWork was going to do to real estate what Uber did to the taxi business, they fought over themselves to place their bets.

Importance of Fundamentals

WeWork’s demise is a reminder that fundamentals tend to win out over time, and that succumbing to hype is not usually wise in the medium- and long-term. Greg Louganis mastered the fundamentals and excelled as a result. His 1986 dive is considered one of the best ever.

Strive to be a Greg, not an Adam.